(This is the second of a two-part blog on pacing my friend, David Nichols, in the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run, one of the toughest running tests in the world and the most storied and prestigious ultramarathon.)

Pacing an ultramarathoner reminds me a lot of ghostwriting or co-writing books. As my friend, veteran ultra pacer and 50/50 marathoner (as in, 50 completed marathons spanning all 50 states) Kenny McCleary, advised me on Facebook before Western States:

Enjoy the day. A pacer has to be part navigator, part psychiatrist, part nurse, part minister, part drill sergeant. But most of all, just be a Barnabas today – an encourager. Only a few souls on this planet have the opportunity or the courage to experience what David gets to live out today. I hope you find the job of pacer/crewmate to be as fulfilling as I have.

With pacing, as with ghost- and co-writing, you check your ego at the door. The only run that matters is his. You do whatever it takes to bring out his best, and take care of him on the trail. No matter how many miles you run alongside, the only accomplishment that matters is your runner crossing the finish line and grabbing that belt buckle.

When we arrived in Foresthill, Dave was 15 minutes ahead of the clock. He’d been almost 10 minutes behind in Michigan Bluff, so he made up 25 minutes in seven miles. Substantial. After weighing in (he’d gained back two pounds) and eating from the quasi-buffet line of hot and cold foods (grilled cheese, soups, quesadillas, cookies, rice balls, etc.) that typifies a Western States aid station, we jogged cross-town and met Don and Craig. They noticed that Dave was a different person than the one they’d seen 90 minutes before. He sat down in the chair, and we went through our crewing ritual … while the clock ticked … and ticked …

Once we left Foresthill, it was pushing 11 p.m. A full night of trail running awaited. Dave and I got into a conversation about the last crew stop. “Do you think we needed to be there that long?” I asked.

“No,” Dave said as we jogged toward the woods.

“I don’t, either. That was too long, especially with the aid station right before it. Maybe we can go faster next time.”

After a moment of silence, Dave said, “I won’t be sitting anymore the rest of the race. I’ll towel off, grab what I need to grab, and go.” Nice sentiment, Dave, but there’s 38 miles left to go … about 11 hours at this pace … and you’ve already gone 62…

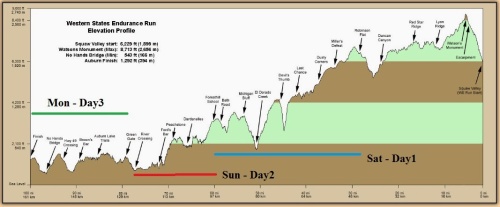

Mountain running, anyone? For 100 miles? This is the course profile of Western States. It hurts to just look at it.

He didn’t sit down again.

At that time, we encountered a runner from Tennessee who couldn’t keep down food or water. She was heaving as we passed she and her pacer to begin another lengthy descent in yet another canyon toward Dardanelles. “You OK?” Dave asked. “Anything we can do?” He and I were thinking the same thing: Stop and help if she needs it. That’s the rule of the road, especially in ultra running.

“I’m OK, I’m OK,” she gasped.

Within minutes, she and her pacer were right behind us, and her spirits were lifting. “You know,” I said, “when I coached high school cross-country, we used to have mid-summer practices. When my kids got sick on the course, I told them they were now officially cross-country runners.”

She thought about it for a second. “So this makes me an official ultra runner, right?”

“You were that a long time ago, but yeah … right.”

She smiled. “Thanks for saying that.” She and her pacer promptly bolted ahead of us. We passed back and forth several times during the next ten miles, creating a nice camaraderie on the course.

Meantime, Dave’s legs had loosened up again, so we ran. And ran. This span between Foresthill and Dardanelles, and extending further out, was dreamlike. We talked, laughed, ran silently and marked each other’s pace while I beamed my headlamp on the trail ahead, and stuck my arm behind me to give Dave coverage with my flashlight. Every time we picked it up the pace, it felt like two guys pursuing something, tracking something … which we were. We were pursuing a belt buckle. I also called out trail obstacles. We marveled at the simple magnificence of running Sierra trails in the middle of the night, no noise other than our footprints and the occasional raccoon, fox, lizard, rabbit or skunk scrambling in the brush, no light other than our headlamps and the bobbing points of light we saw on the trails ahead of us. They looked like little stars dancing on earth. What could possibly be better than running with a friend in such peaceful, desolate surroundings?

I’m sure Dave had an answer: Being done.

The Ford’s Bar aid station, lit up in the wee hours of the morning. It was a welcome sight after the two miles that preceded it.

The approach to the Dardanelles aid station was marked with Halloweenish signs and a couple of cut-out ghosts (nice). The scene reminded me in a certain way of the R.I.P. tombstone sign we planted at the two-mile mark of our Carlsbad High School cross-country course in 1976. We put it on the middle of a steep, steep incline, nicknamed Riggy HIll (as in, Rigamortis Hill; I returned in June to run it again a few times to prepare for Western States). We averted our eyes; opponents stared at it and let the thought sink in as their legs wobbled. Game, set, match. “You guys were great hill runners,” my coach then and now, Brad Roy, recalled. We were also good psych-out artists, Brad. A funny memory, conjured up at 1 a.m. 600 miles and four decades away…

At Dardanelles, a volunteer, a veteran of a couple dozen Western States runs, pulled me aside as he watched Dave hover over the food table like a famished refugee. “Keep your aid stops to a minute,” he said. “That’s all he needs. Get in, get your food, get your water bottles filled, ask us about the next section of trail if you want, then get on with your run. You don’t have time for anything else.”

Great advice. We heeded it on every subsequent aid stop.

The next section was brutal, in every possible way: switchbacks, rocks and roots, tremendous drop-offs from canyon walls to the American River, steep inclines and descents, runoff grooves in the middle of uneven trails, sand, creek crossings … in other words, difficult to ride on horseback, let alone cover by foot. Especially at night. The frustrating part was that Dave had his second wind (or maybe his third or fourth; you gain several “second winds” during ultras), so we wanted to run … but couldn’t do so steadily. Every time we found a rhythm on the trails, clicking off a half-mile or so, the course threw something else at us.

The Rucky Chucky crossing — a cooling, refreshing walk through the American River always helps before tackling the final 20 miles.

During one stretch, we opened up the pace on a pencil-thin stretch of trail, me leading the way. I looked to the right; a nice Manzanita thicket. I looked left; sheer blackness, nothingness. “Bob, is this one of those thousand-foot drop-offs we’re running next to?” Dave asked, his voice tinged with concern.

Peering into the future: the scene awaiting us in Auburn — large crowds packing Placer High School stadium and the finish line.

Gulp. “You know what one of the great things is about running at night?” I didn’t turn around; I didn’t want to face him. “You can’t see anything but what’s in front of you.”

We ran directly into my headlamp beam, taking advantage of the night. The advantage? Were it daytime, we never would’ve run on thin single-track with such a precipitous drop-off. In fact, for the past two months, I’d broken into a few wee-hour sweats thinking about how I would pace Dave in these sections, and keep us both from sliding off the hill. Scrambling down a cliffside to retrieve a fallen ultra runner wasn’t on my agenda, though it was certainly on my mind. We kept running.

At miles 72 and 73, we didn’t run much at all. Survive is more like it. We heard Led Zeppelin’s “Over the Hills and Far Away” (appropriate) blaring from the nearby Ford’s Bar aid station. As we ran along the top of the hill, the music – and aid station – sounded a few hundred yards away. Double the acoustics in a canyon, so say six hundred yards. No more. We were pumped, now a good half-hour up on the clock, making it happen…

Yeah, it happened. The course happened. One of the nastiest curve balls of the entire 100 miles snapped at our legs and almost took Dave’s spirit with it. When did Clayton Kershaw show up? We found ourselves descending through a Manzanita grove, on slippery, chalky white hardpack trail with a runoff groove down the middle. The descent kept going… and going… and going… My quads hated the punishment, and I’d only gone 20 miles. Dave’s legs were practically on fire. We adjusted our foot strike posture and leaned back on our haunches, almost like skateboarding, so our butts could absorb much of the stress.

In the next three-fifths of a mile, we descended 1,200 vertical feet. Insane. It would all but fry a mountain goat. We heard the music again, and gave each other a smile and an “attaboy, we deserve this aid station” glance.

The course belly-laughed at us. After running out our soreness on a quarter mile of beautiful, slightly sandy trail, we faced the second half of this crucible: a fire road climbing into the sky, twisting and bending, its banks as steep as some racetrack turns. We grunted and groaned up 400 vertical feet in the next quarter-mile – then hit a short, steep downhill that dumped us into the Ford’s Bar aid station.

Remember all that time we’d gained? Well, nothing like a one-two punch to send us back into scurry mode. We loaded up at Ford’s Bar, and a gracious volunteer ran our refilled water bottles to us so we could keep moving. Unfortunately, the hills sapped Dave’s legs again, and he found it very difficult to run. We jogged a few times in the next couple of hours, but he couldn’t get it going, even during our final two miles before the Rucky Chucky crossing, when sandy bottom trail and mostly flat fire roads offered an opportunity to pick up time. I wanted to push him, as I had in previous stretches, but common sense kept telling me, “He needs to save it for the final 20 miles.” So, we power walked or did the marathon shuffle (the stride of a three-year-old, familiar on marathon courses the last few miles after people ‘hit the wall’).

Finally, we passed the Rucky Chucky metal gate, ascended a small hill, and dropped into a raucous river-crossing scene, at which runners and pacers cross the American River by holding onto a cable. We ran to our crew, now just 10 to 12 minutes ahead of schedule but far better than his status at dusk. As Dave walked through the aid station, I told Don, “He’s decided not to sit again until he’s done. His legs tighten up too much and he won’t be able to loosen them up.” Then I discussed Dave’s condition and mental acuity with Craig; his focus was still very strong, much stronger than some other runners I saw out there.

“I’m gonna have to push him hard the last few miles,” Craig said as we finished.

“He responded every time I pushed him hard,” I said. “We conserved energy the last five miles after these God awful hills … I’ll tell you later. He knows what needs to happen. You’re the man. Bring him home.”

My pacing was done. I wobbled around, spent after more than seven hours of trail running, wondering how in the world these people do it for 18, 24, 30 hours in a row. I always admired Dave, but now, my admiration went through the roof.

Dave prepares to enter the stadium, with brother Don running alongside. Our ace pacer on the last leg, Craig Luebke, is cheering at the gate.

Six hours after Craig set out with Dave, and 90 minutes after seeing our glassy-eyed, exhausted runner at the 93-mile crew stop, Don and I arrived at the Placer High School Stadium in Auburn. What a scene: a thousand people on hand, the announcer calling out finishers, families and crew running into the stadium and around the track with their warriors, the monumental test complete. It had been a night and most of a morning since the overall champions, Rob Krar and Stephanie Howe, crossed the line. Krar became the second runner to ever break 15 hours in the event’s 40-year history, running 14:53:22, while Howe won the women’s division in 18:01:42, the fourth-best women’s mark all-time. They were magnificent, as were Ian Sharman and Kaci Lickteig, whose performances enabled them to claim the series titles in the 2014 Montrail Ultra Cup, a mini-tour of six ultramarathons culminating in Western States.

Western States champions Rob Krar and Stephanie Howe talk trail story after their near record-breaking performances.

Lickteig is known in the ultra community by her nickname, “Pixie Ninja,” perhaps the best athlete nickname I’ve heard in nearly 40 years as a journalist. I asked Stephanie Howe about it. “It’s perfect,” she said. “Kaci is an assassin out there.” Case in point: she won all eight ultras she entered in 2013, came to Western States despite basically no recovery from her previous ultra (a win) – and placed sixth.

Our runner was magnificent as well. Dave took his victory lap at 10:45 a.m., flanked by Don and Craig, with me shooting photos from behind. Tears had been in Don’s eyes for twenty minutes; now, they also came to mine.

As we moved around the track, I thought of all the hopes, doubts, aches, pains, discomfort, dehydration, sunburn, scratches, bites, blisters, mental self-arguments and talks with Jesus Dave had in the past 29 hours, alone or with one other person on a trail that gave no quarter. I thought of Dave and Don, running the final 600 meters side-by-side, brothers in life and in this pursuit. For them, six months of planning and training culminated with the final piece of the 100th mile. It was an incredibly moving moment.

What it’s all about – the Nichols brothers, moments after Dave crossed the finish line. A very touching moment.

After Dave crossed the line in 29:49 and received his medal, we waited 90 minutes for the presentation of the coveted belt buckles. Dave stretched out on a brick retaining wall, dead to the world. Don and I had some fun, taking a couple photos of our runner laid out on the rack, then Craig and I walked to the refreshment stand and grabbed breakfast. Craig hadn’t eaten meaningfully in a day, either, having somehow marshaled Dave’s energy enough to get him home in plenty of time. I still don’t know how Craig pulled off his pacing feat. I would imagine a few whipcracks accompanied the encouragement as they passed through Brown’s Bar, the Auburn Lakes meadows, up a final nasty hill at the 99-mile mark (that hurts just writing it) and into town.

Finally, it was time for Dave’s crowning moment. We helped him to his feet and took a slow 200-yard walk to the awards tent. A few steps after reaching the grass, Dave winced. “Oh man, a hill.” I looked down. There was the tiniest bump on the football field, maybe six inches top to bottom. For a man who just completed something only a sliver of humanity would even attempt, and whose legs were barely functioning, a six-inch bump is a hill.

After watching the elites grab their prizes, for averaging 8:30 to 9:00 per mile for the whole 100 miles, we cheered madly as Dave received his belt buckle. It was his turn to plant the flag on the summit.

Dave collecting his belt buckle and accepting congratulations from Tim Twietmeyer, who won Western States five times among his 25 sub-24 hour finishes in the race.

Then I remembered something: Dave is also a two-time Boston Marathoner. How many people have run both Boston and Western States, the most prestigious annual events in marathon and ultramarathon? In 40 years, only 7,500 runners have finished Western States – many of them repeat or multiple finishers. So let’s say, liberally, 6,000 different souls. Of those, how many own Boston unicorn medals? A thousand? Two thousand? Certainly not more. He joined an exclusive club.

Dave repeatedly credited all of us as a team, a nod to his humility. We appreciated his words, but sloughed them off. This is your barbecue, big guy. While Don, Craig and I became brothers-in-arms through our seamless support operation, that’s the extent of what we were on this weekend: support for the man with the belt buckle.

And with that, your hosts for this 100-mile Western States odyssey sign off, with our lead warrior, Dave Nichols, second from the left.